In the 1984 classic Sci-fi movie The Terminator director James Cameron first introduced us to a futuristic corporation called skynet; an artificial intelligence system that will spark a nuclear holocaust, a struggle with humankind to take over the planet many years into the future. When I first watched this movie as a kid I was mesmerized by the storyline, and of course those mind-blowing 80’s special effects. It was a movie. A fantasy. Never once did it cross through my pre pubescent brain that anything even remotely close could occur in my lifetime.

Now, 34 years later, with the steady development of AI it seems at least plausible, if not likely, that technology is soon approaching its highest precipice yet of the unknown, and the deep chasm beneath is teaming with potentially vexing problems for the world as we know it. The real question is will all of this technology solve as many problems as it might create?

As is often the case, fiction mirrors real life, at least to some degree. Sci-fi books and movies that seemed incredibly futuristic in their time seem that much more possible as I get older and technology steadily progresses. Things have a much more subtle arch of progression in real life, however. If we stop to carefully consider where we are now as opposed to 34 years ago can it be denied that machines and computer technology play a much more integral role in the daily lives of society today? If we’re realistic, I don’t think so. As these changes take place over the course of time, however, we barely notice it until one day we stop and really reflect on how much are lives have changed from when we were kids, and even more so from the lives of our parents, and yet even more startling still, in contrast to those of our grandparents.

The difference, at least to me, is that our forebears used the technology and machines of the time to get places, to create more efficient production, transportation, and to build things and thus move the world forward. Not unlike us. Although our version of the world and it’s progress looks vastly different. Computers certainly make the world run more efficiently in many, many ways. But along the way the scale seems to be shifting as well, perhaps even beginning to approach a tipping point in the opposite direction where technology is gradually coming to consume, if not outright own us. Any remaining doubts I had about this, were easily put to rest after accidentally leaving my smart phone at home for one single work shift. It might have been interesting If I’d bothered to count the number of times I found myself reaching for it like an incessant itch. At first, you feel a little naked, much the same as you might if you left your wallet at home, or if you want me a bit more dramatic, as if someone just hacked off your right arm. So… assuming we’ve all experienced this at some point, whether intentionally or by accident, the questions are for each of us to consider. Do we own it, or does it own us? How long can we manage to go without it?

A recent study estimated that Americans check their phones on an average of two hundred times per day. This may seem like an unrealistically high number until we take a closer look around us. Everywhere we go, everywhere we look, people are staring at screens. People run into each other on the streets because they don’t look where they are going anymore lest they pull their eyes from the lure of the screen. These devices fill the empty spaces of our lives, the spaces we used to use for noticing things and making astute observations. Of course, as I may have hinted in the previous paragraph, I am just as guilty of this as the next person.

In George Orwell’s brilliant post world war 2 dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty Four he writes about a world where his characters most intimate private moments are often violated. People are tracked and speech is monitored. Isn’t this in some sense happening today thanks in large part to those smart phones we carry with us everywhere and hold so dear? Everything we see and hear is based on our speech patterns and search engine algorithms and are then boldly and aggressively used to manipulate and sell us stuff. And it all works like a charm.

So what’s the answer? One thing we can be assured of is that technology isn’t going anywhere. It’s only going to get faster and smarter and more virtually interactive; the proliferation of information easier to over consume and become more dependent on. It is us who have to learn to put the brakes on, to discipline ourselves, to be more discreet, to protect what we can of our privacy, do the necessary research to make careful decisions, and perhaps most importantly, to know when to turn off and just give our minds and bodies the respite it needs from all this noise.

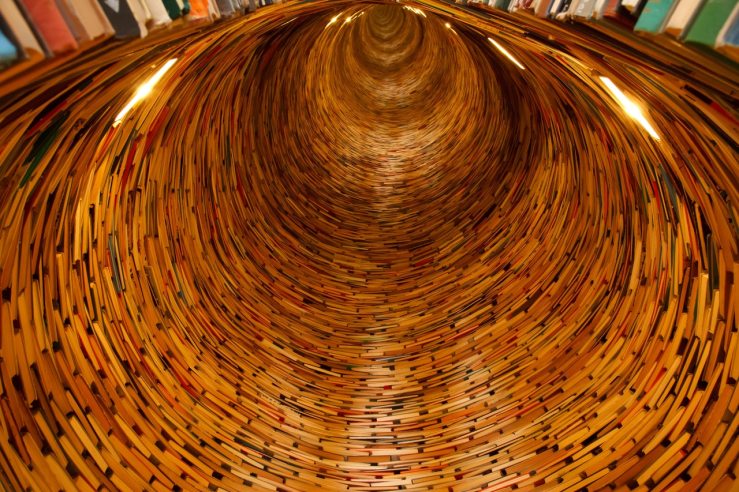

Perhaps one way we can do this is by blocking out certain portions of the day for just shutting off. Separate ourselves from our devices. We could start by committing to put them away and silencing them while we’re conversing with someone, or at a restaurant, or while watching a movie, or spending time with family. We can choose to just be in the moment rather than distracted by the endless notification beeps and blips and cute little ringtones. Then, maybe we could try this again while taking a walk alone in nature, or through our neighborhood, or go for a run, swim laps, read a book, a real physical book that we actually have to hold up to the light and turn pages. We could do this while we work on art projects, or hobbies, or listen to music, or meditate. We can choose to fully focus on the experience of these things in the moment. The possibilities are endless for escape.

Maybe all we have to do is commit to the practice of shutting off a few times a day. Obviously many of us can’t do these things during a work day, I get it, but when time is ours we can choose how much of that time we have to be staring at screens, whether it be gaming, answering emails, surfing the net, or perusing social media. All of these platforms are very useful and have their place, but it is also no secret that they all can, and often do, contribute to increased stress and anxiety levels. We can, however, establish a healthy balance just as with anything else. These platforms do not have to own us. They do not have to command our attention during all waking hours of the day and night. We can draw boundaries the same as we do when choosing when and what foods to eat for optimal physical health.

Recent sleep studies have concluded that turning off devices or staring at blue light for sixty to ninety minutes before going to bed can significantly improve the quality of our sleep. How many of us do this? I sure don’t, but I intend to give it a shot. It seems the importance of this cannot be overstated, especially for someone like me who doesn’t get a lot of sleep to begin with it only makes sense that the sleep I do get be of the highest quality possible for optimal cognition and focus throughout my waking hours.

As humans we have proven time and again our incredible aptitude for adaptability. As technology grows and distractions become more and more prevalent is it not left up to us to figure out a way to take back these precious present moments? After all, the present moment is the ONE thing we truly own, and it is all we will ever have to make the worst or best of.

something interesting to watch on television I came across a Netflix original documentary titled

something interesting to watch on television I came across a Netflix original documentary titled